Small Town Offers ‘Sign’ Of Welcome To Refugees In The United States

Biking one day in the city of Harrisonburg, Virginia, nestled in a valley in the Shenandoah Mountains of the eastern U.S., 33-year-old Pastor Matthew Bucher tumbled and fell.

Bloody and sore, he found himself in front of the local mosque. He looked up and read a sign.

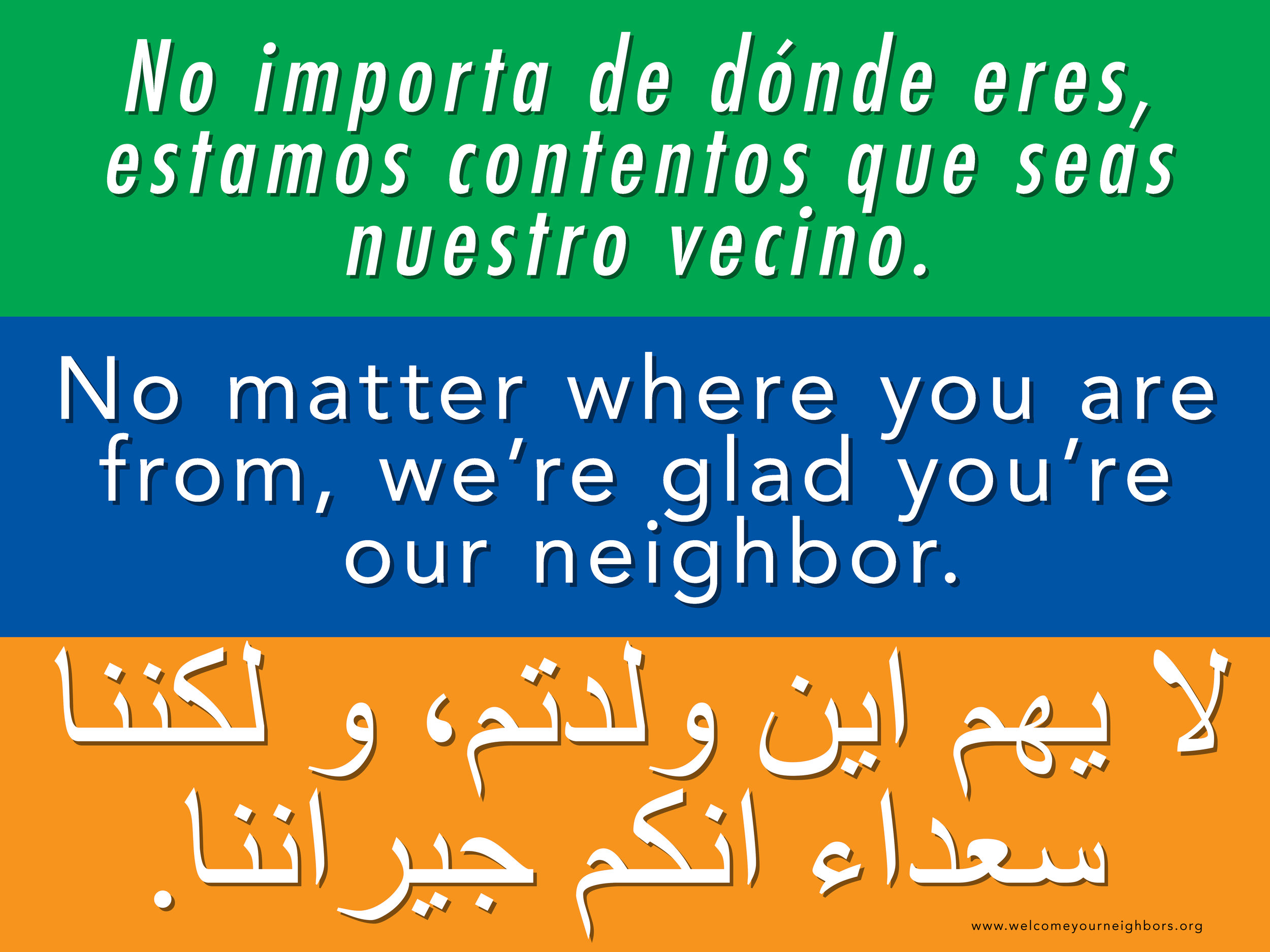

“No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor,” it read in English, Spanish, and Arabic.

Bucher understood because he had written that sign - in all three languages.

“Suddenly, I knew the hope the sign offers,” he said. “I was the one in need of help, switching roles.”

The sign was born 15 months earlier, during the August, 2015, Republican presidential debate. Anti-immigrant hectoring was a prominent feature, and Bucher led his small congregation at Immanuel Mennonite Church to do something about it.

Rather than filling neighborhood yards with political signs backing one candidate or another, Bucher’s church created a sign of their own.

“I was shocked at the rhetoric used against immigrants,” he said. “So I thought to put out a sign of welcome. Spanish speakers in the church helped, as did Arabic friends.”

That first sign in front of his church two years ago has since multiplied into an estimated 100,000-plus throughout the country, said Bucher.

The sign is recent, but its heritage extends back almost four centuries.

Mennonite Christians know what it means to be strangers. Driven from Switzerland in the 17th century, the persecuted Anabaptist community, from which the Mennonites descend, found refuge in Pennsylvania. One hundred years later many of those families relocated to the Shenandoah Valley.

Bucher, a Pennsylvania native, became the pastor of Immanuel Mennonite one year before the presidential debate. But from 2007-2011, he lived as a stranger himself, the only American in the small, Upper Egyptian city of Qusia, 170 miles south of Cairo. Teaching English in partnership with a Coptic Orthodox bishop, his sojourn was a transformative experience.

“I received hospitality in Egypt, and here in Virginia I have been accepted and trusted as a pastor,” he said. “I want to extend that (hospitality), just as Jesus did. He and his parents were cared for as refugees, too.”

Harrisonburg is a fitting place for hospitality. Census data states the population of 50,000 residents is 16.7 percent foreign-born. Students in the public schools come from 46 countries, including Iraq, Jordan, Honduras, Mexico, and Ukraine.

Yet there have been only four police officers killed in the line of duty in the town since 1959. Nicknamed “The Friendly City” since the 1930s, Harrisonburg is also an official Church World Service refugee resettlement community.

“Listening to the current American national dialogue. . . one would assume that mixing nationalities, religions and ethnic groups in such close quarters would produce enough emotional tinder to fuel a blaze of angry divisions and open fighting in the streets,” wrote resident Andrew Perrine in the Washington Post. “Yet it does not.”

Instead, Bucher’s signs have found a home. The green, blue, and orange background was chosen so as not to correspond with any national flag, and 300 signs were initially distributed through six area Mennonite churches in March 2016. Another 300 were sold later at a local fair, next to the church’s tamale stand. By October, one month before presidential elections, another 1,000 were printed.

They sold out within a week.

That month the church created a Facebook page. Overwhelmed by interest, in December they created a website. Signs sell for $21.95, including shipping, but a free download is provided to print locally.

“That first sign in front of Matthew Bucher’s church two years ago has since multiplied into an estimated 100,000-plus throughout the country. ”

Money from proceeds is donated to the Mennonite Central Committee, the local New Bridges Immigrant Resource Center, and the Roberta Webb Child Care Center hosted at Immanuel.

Anyone selling in their own communities (usually for $10 with local pickup) is encouraged to donate to the charity of their choice. Unless they just give them away, as did a 68-year-old Buddhist, Kathy Ching.

Ching arrived from China in 1974 and ran a restaurant in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, for 40 years. During that time she helped 15 employees immigrate to the U.S., but now says of President Donald Trump, “He’s not letting people in.”

“Why do they want to come to America?” asked Ching. “Because their own countries are in trouble, and they want freedom.”

She learned of the sign through a neighbor, and purchased four at St. John’s United Church of Christ.

Pat Rieker made them available. A longtime member of St. John’s, Rieker was so pained at the anti-immigrant sentiment in America she felt her health was suffering. Feeling she had to do something, she mobilized her church after seeing the signs at nearby Plains Mennonite.

“It made me feel I was spreading some kind of message of hope and inclusion amid an atmosphere of hate,” she said. “To me, this is not the message of Christianity.”

Plains Mennonite in Hatfield, Pennsylvania, was one of the first in the area to display and distribute the signs. Associate Pastor Paula Stoltzfus had family and friends in Harrisonburg and followed the campaign on social media. She informed the church, and with a history of welcoming refugees from Sudan, Iraq, and the Congo, it mobilized easily.

“It was an idea whose time had come, reminding us to be a good neighbor,” said Pastor Mike Derstine. “This should not be a political issue but an expression of our faith.”

Similar grassroots stories have now resulted in 70 volunteer distribution centers in 32 U.S. states. Two churches in Idaho have circulated over 500 signs. In Portland, Oregon, the sign appeared at a memorial for two men who were killed in May while intervening to stop a white extremist harassing a young Muslim woman.

In addition to the signs at the local mosque in Harrisonburg, Bucher has sold to the synagogue and several atheists. Though the initial distribution moved through Mennonite churches, he estimates they only total 30-40 percent of total reach.

“I never asked my friends what religion they are. It doesn’t matter,” said Ching. “We are of different religions, but we all have a good heart.”

Yet it is Bucher’s Anabaptist heritage and Christian commitment that drive his particular service. His church’s motto is: Real people following Jesus’ radical call to love and service.

One local Baptist church pastor asked to meet him, suspicious of a liberal agenda. In the tense discussion that followed a spilled glass of tea helped them break the ice. But the conversation only turned once the pastor became convinced this Mennonite really did love Jesus.

“We must speak of power and privilege, sure. But many on the other side cannot accept Trump or his followers, either,” Bucher said. “Stand against violence and bad leadership, yes. March and demonstrate, yes.

“But be transformed by the love of God. Change is hard, but it is what we are called to do together.”

Bucher tells a story from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a traditionally rural Mennonite community now with a majority non-Mennonite city center. The municipality has resettled 20 times more refugees than the rest of the United States.

A lady put one of Bucher's signs out on her lawn. She came home one day and found a Syrian on her front steps. Speaking no English, the hijabed woman took her neighbor by the hand and led her across the street into her own home.

Opening up the computer, she typed in Google Translate.

“Thank you so much,” read the neighbor. “Your sign made us feel welcome. We are glad this is what America is about."